Angel Fernandez Saura

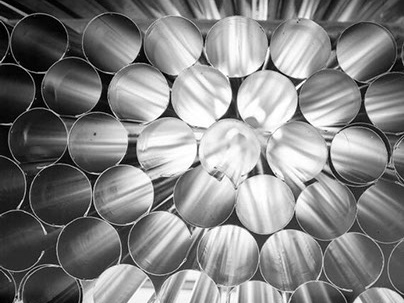

An avid look, creative thinking. Enric Mira A photograph is not an accident, it is a concept. Ansel Adams1 If we had to determine the historical moment in which we could find the origin of the renewal of the photography in Murcia, it would be, without any doubt, that which covers the last years of the seventies. In those years, the creative interests of some young photographers gave rise to the creation in Murcia of the “Colectivo Imágenes”. It was 1978 and they were just a few, hardly seven photographers: Ángel Fernández Saura, Paco Salinas, José Hernández PIna, Ricardo Valcárcel, Juan Ballester, Saturnino Espín and Antonio Ballester. As a group and as individualities, they distanced themselves from the creative anonymity of the photography practised in the photographic associations, which were in full decline, but they also grouped together against the formal routines revealed by a meagre professional photographic activity. More than a style or an aesthetics, they were together because they convinced that the photography was a means with its own language and, therefore, a means that could rightfully share the arena of contemporary art. From their own aesthetic approach, the members of this group turned the photography into a form of artistic expression and their images became known through different photography exhibitions. That was not an isolated, chance happening, the “Collectivo Imágenes” were joining both the transformation of the Murcian plastic art scene and the avant-garde impulse of the young Spanish photography, represented from the very beginning of the decade by the journal called Nueva Lente. By then, there was an aggressive air of freedom in all the expressions of the social and cultural life of a country which started its democracy after the end of Franco’s dictatorship2. Till its dissolution in 1982, the “Colectivo Imágenes” covered the creative interests of its members. From that moment, the diversity of its aesthetic thinking favoured that each of the photographers’ career developed in different ways. At the beginning of the eighties, Fernández Saura started to delimit his topics and to define the visual approach which characterizes all his photographic production. His arrival in New York City in 1987 marked his creative growth, intensifying learned ways of seeing, but also discovering new realities to transfigure through the oblique look of his camera. The different topics that Fernández Saura has developed in selfportraits, the city, its inhabitants and architecture, the abstract visualizations of a concrete reality, the oneiric images and the photographic image as appearance and as sign of the real. A rich variety of topics which gather traditional genres in painting and innovative forms, inheritor of the visual language of the avant-garde, but which meet, however, a well-defined aesthetic-photographic approach: a selective and organizing view which extracts and fragments the objects –to the point of being almost unrecognizable– by means of a careful compositive execution of the image. Selection and composition, objectivity and abstraction, reality and surreality are the terms which, in a sharp dialectic, articulate the creative way in which Fernández Saura watchs reality and thinks about it through his photographic images. The act of taking a photograph, in this sense, is not just to reproduce the visible, borrowing Kandinsky’s expression, to make reality “visible” through its appearance and the subjectivity of that who photographs them. Selection and composition. To the photographer, the choice of the object is a creative act in itself3, it is the beginning of the process of creation. Reality is something in an incessant search and, therefore, in an incessant discovery. Fernández Saura’s perceptive sensibility examines nature –from its microscopic configuration to the general one–, the human body or the urban fabric. A landscape or a skyscraper, a window, a gesture or a face are a provocation to his gaze. They are elements ready to be submitted to his visual intelligence, more to be discovered than to be beautifully described, through a new visual appearance, their most intimate nature. In order to do that, the photographer must choose one out of the infinite points of views of the object –usually that which can disconcert our perceptive conscience– sectioning it from the spatio-temporal continuum of the real and emphasizing its singularity. This is so in the series titled “Ventanas” (Windows”) and “Depósitos de agua” (Water tank), where the mainly fragmentary nature of the photographic image works, as if it were a centripetal force, as the (re)organizing principle of the iconic forms and their meanings. The windows where the inhabitants of the buildings are leaning or the water tanks which dot about the roofs and flat roofs of New York are elements which Fernández Saura has rescued photographically from their anonymous and grey contextual reality. They are windows that mark the limits between the private and the public, sometimes with blind eyes and sometimes with discreet eyes; water tanks that show a sculptural beauty in their structure of untimely forms. Isolated objects which act as scat tered clues in a story impossible to be told4 but which exercise their nature as aesthetic symbols and their visual power as icons in the metropolis of New York. Even when the static composition of the photographic fragment is connected in a series of images in “Secuencias” (sequences), that uncertainty is patent, a plot uncertainty in the images in favour of a certain visual enigma. This series represents a group of photographs taken from above of people walking on the street. People who come and go in an improvised parade, conforming a sequence without an end or a narrative order. Still after still, the pedestrians project their shadows on the bright asphalt as if they were the scribble of an uncertain writing. If one looks at the work by Fernández Saura, one knows for certain that the photographer knows intuitively when he is in front of the right object in the right time. And this is not by chance, due to the fact that, as Bernice Abbot (who photographed New York passionately in the 30s) said, the selection of a content which is appropriate for the image “is the result of the delicate joining of the trained eye and the mind with imagination”5. Fernández Saura has that analytic and, at the same time, amazed gaze, a gaze which is evaluating and imaginative, which is able to extract a hint of eternity from the contingency of the city and an aesthetic sense from the chaotic transformation of its daily nature. Objectivity and abstraction. Even though the figurative iconic language is consubstantial to the photography, many photographers have been tempted by a photographic image of abstract representation in which the referents dissolve in the purely formal elements. Some photographers, such as Otto Steinert, founder of the Subjective Photography during the second European post-war period, saw in this photographic de-materialization of the object the expression of the “absolute photographic creation in its freest aspect”6. Abstract photographic creation whose sense was close to the non-representational approach of the constructivist and supremacist pictorial abstraction and whose best examples can be found in the stills that Moholy-Nagy called “painting with light”7 or in the contemporary chromatic chemigrams by Pierre Cordier. We must admit, though, that this expressive method has been very unusual in the history of photography. However, the fragmentary nature of the photographic frame, no matter whether it is combined with a close approach to the object or with the furthest distancing from it, has showed signs of the ability of the photography to get images without an immediate or apparent analogical sense. Unlike what happens in some pictorial abstraction, in the photographs by Aaron Siskind or Florence Henri, and in so me images by Paul Strand, what shows, from an original point of view, that other vision of reality as abstract, is not the elective reduction of iconic elements in the referent but the contextual reduction or isolation. In a strict sense, the idea of a photographic abstraction is a concept of a contradictory logic, due to the fact that, whereas painting devises its forms from the conceptual relationships and not from the material entities, in photography the abstract forms are the representation of an indexical realization of the referent: the light mark of a physical reality which is materially present. However, apart from this essential difference, the abolition of the descriptive link with the world and the reduction of its iconic immateriality are concentrated, most of the times, towards a meaning of a spiritual or mental nature, both in painting and in abstract photography. Fernández Saura has ventured to do abstract images in different moments in his career as a photographer. In the middle 80s, inspired by Mondrian, he took a series of polaroids forming geometric and colour effects. Then came a macroscopic approach to the epidermis of the objects, plants and minerals, which led to some photographs whose chromatism, texture and composition provoked the effect of an abstract pictorial execution. This style of photographic creation resulted in the series “Vertical” and “Signos de Guerra” (War signs), offspring of his stay in New York in 1987. In the latter, influenced by the pop aesthetics of the paintings by Jaspers Johns, Fernández Saura focuses on the graphic elements painted on the fuselage of the American Army Fighters. These icons of the war power of the United States, framed in a slanted way by the camera, become images in a double game: as aesthetic compositions and as conventional signs rescued from reality. There are few things that embody so clearly the economic, technological and cultural identity of the 20th century as the skyscraper. They are the most ostentatious face of capitalism and one of its most challenging technological displays but, at the same time, they are also its most beautiful and admired objects. Alfred Stieglitz, Berenice Abbot, Walker Evans or Ralph Steiner are among those who discovered photographically the impressive and defiant image of the skyscrapers in New York. With his photographs in “Vertical”, Fernández Saura testifies to the tempting power of these buildings, of their enigmatic presence of hermetic object. Our photographer’s avid look was captivated by the rational architecture of the skyscrapers, by their orthogonal forms and their calculated geometries, by their polished surface that, as a screen, reflects the incessant changes of all that surrounds them, what turns them into static canvases. Adequately framed by the camera, these geometrical forms turn the certain body of the skyscraper into an abstract entity... dematerialized and light. If in abstract painting the dematerialization of the object shows a jump towards spirituality, in the architecture of the skyscraper, the verticality of the structures and the blurring of the gravity of their materials express the utopian longing of merging with the sky and of transcending the worldly nature on which they are built on. The photographs by Fernández Saura recreate and interpret iconically the building forms of the skyscrapers rather than testifying to them. Out of the urban landscape, with their monolithic unity fragmented, these buildings turn into a plastic material dominated by the photographer’s expressive purposes: sublimated skyscrapers in that which Otto Steinert described as the “object with a creative intention”8 Reality and surreality. A good photographer is that who knows how to recognize objects and objective forms which, when photographed, give rise to an image able to suggest emotions leading the viewer towards his inner world. That was the idea which supported the concept of “equivalent”, thought by Alfred Stieglitz. “Equivalence, as Minor White specified, is a function, an experience, but not a thing”9. But this is not just a perspective psychology matter; we could almost say that it is also an ontology matter on the photographic image, as it shows us how the automatic register itself of the photographed reality breaches surreality... “What could be more surreal, wonders Susan Sontag when thinking about the photographic image, than an object which virtually produces itself with a minimum effort, an object whose beauty, whose fantastic apertures, whose emotional weight will surely be enhanced by the accidents that happen to it?”10. The photographs in the series “Zooilógico” (Zooilogic), taken in the Natural History Museum of New York, show how this attack of the surreal takes place inside the glass cases where the stuffed bodies of wild animals are displayed. With an exotic landscape as a background, surrounded by a filtered light, the static gesture of the animal provokes a disconcerting mixture of reality and unreality. Roland Barthes had already seen in the photographic act a taxidermy operation when he claimed that “everything framed dies completely”11. But when the immobility of the photograph anaesthetizes a being which is already inanimate, what happens is that it blurs the distinction between the living and the dead… as in the dummies in the shop windows in the old Paris taken by Atget or as in the orthopaedic prosthesis that captivated Stirsky. If, in an earlier stage, Fernández Saura tried to make an oneiric image by means of the superposition of several negatives, in “Zooilógico” the surreal and oneiric density of photography does not come from the manipulation of the image but, paradoxically, from the direct and immediate shot of reality, an image which now becomes a traitor of its traditional documentary function. Not in vain, Brassaï claimed that there was nothing more unreal to him than the real. Perhaps his collection of self-portraits does not move away too much from the basic reasoning of the interpretation we have already set out. What is the reason then for that reiteration of images of his feet from above as a kind of self-portrait? The absence of a face breaks a dominant logic in the (self)representation of the subject in the western culture, in a gesture that reminds that which surrealists such as Boiffard, Bellmer or Kérstez used. Through a strategy of displacement around an identity, of a splitting of the subject from inside, Fernández Saura offers an oblique vision of his body and of himself. It is just the opposite as in his photographed nudes, where the displayed feminine body is evident, full of eroticism and body beauty, as a self-sufficient and emphatic organic symbol. These self-portraits, ironically ugly, live on a dialogue between otherness and identity where the bodily and the mental, the physical and the immaterial are interchangeable. That is why the idea of interpreting the self-portrait as a hiding of the self does not seem to make much sense. Perhaps, what is really revealed in this metaphoric game of substitution and subjective estrangement is the photographer’s privileged gaze as a vision of himself and, by extension, of the reality registered in his photographs and, at the same time, produced. In the end, reality and conscience are fed back in Fernández Saura’s work. It does not matter if they are skyscrapers, water tanks or nudes; his photography changes their entity as dumb and indifferent beings, showing them as support and means –as sign and writing– of a meaning which is different from its material literality. 1.- Adams, Ansel, “A personal Credo” en Newhall, Beaumont (ed.): Photography: Essays & Images, Nueva York, MoMA, 1980, p. 260 2.- Cf. Mira Pastor, Enric: La vanguardia fotográfica de los años setenta en España, Alicante, Instituto de Cultura Juan Gil Albert, 1991 3.- Roh, Franz in “Mecanismo y expresión: esencia y valor de la fotografía” in Fontcuberta, Joan (ed.): Estética fotográfica, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1984, p. 13. 4.- We appropriate John Szarkowski’s idea on the narrative poverty in the photography on display in his text for the exhibition The Photographer’s Eye, New York, MOMA, 1966, p. 6. 5.- Abbot, Berenice, “La fotografía en la encrucijada” in Fontcuberta, Joan (ed.): Op. cit. p. 185. 6.- Steinert, Otto: “Sobre las posibilidades de creación en fotografía” in Fontcuberta, Joan (ed.): Op. cit., 226-227. 7.- Moholy-Nagy, László: “Compendio de un artista” in Laszló Moholy-Nagy, Valencia, IVAM, 1991, pp. 413-414. 8.- Ibidem. 9.- White, Minor, “Equivalencia: tendencia perpetua” in Fontcuberta, Joan (ed.): Op. cit., p.210. 10.- Sontag, Susan: “Objetos melancólicos” in Sobre la fotografía, Barcelona, EDHASA, 1981, p. 63. After Susan Sontag’s seminal analysis on surrealism, Rosalind Krauss has done a very precise analysis on the affinity between the photographic jeans and the surrealist aesthetics. Cf. Krauss, Roslind: “Los fundamentos fotográficos del surrealismo” in La originalidad de la vanguardia y otros mitos modernos, Madrid, Alianza, 1996, pp. 101-132. 11.- Barthes, Roland: La cámara lúcida. Nota sobre la fotografía. Barcelona, Piados, 1990, p. 106.